Practically every corporate boss these days has it on their to-do list – coming up with a business purpose beyond making money. Most of the time they feel it’s a bit too touchy-feely an assignment when the only thing they really care about – what they get handsomely rewarded for – what the board and shareholders and financial analysts expect of them – what they were trained to do in B-school – is generate faster growth and higher earnings. But they also feel the growing public pressure to position their business as a socially responsible corporate citizen. To be seen as heroes and not villains. And so they go through the motions of defining their business purpose.

The CEO might choose to hold a facilitated retreat amongst the executive team and define that purpose behind closed doors. Or the job might be handed to marketing, thinking it’s nothing more than a public relations initiative. Or they might mistake it for a Corporate Social Responsibility campaign. The outcome, in every case, is exactly the same: a lame purpose statement followed by an ostentatious launch event and internal rallies to inspire the troops, accompanied by some external fanfare, just so the public is aware. But then that initial surge of enthusiasm fades away. All that is left, a year or so later, is a wall poster, a revised “About Us” page on the web site, and communication slogans from a now dormant ad campaign. Back to business as usual.

No wonder the critics of brand purpose are so shrill in their opposition to it. The acerbic Marketing Week columnist Mark Ritson calls it “moronic”. Another equally churlish marketing expert Byron Sharp accused proponents of learning their economic history in art school. And of course activist investors loathe the idea. Even Unilever, whose commitment to sustainability is undisputed, came under attack, mocked by one large equity investor as “losing the plot”.

Yet, despite the nasty criticism, there is a business purpose to having a brand purpose. Because the public perception today is that corporations are the enemy, responsible in one way or another for many of the ills in society, from growing income disparity to workplace discrimination to environmental pollution. So corporate reputations are at stake. Companies which act as pariahs just put social stability at risk which is never good for business.

The long-held Friedman doctrine that business has only one purpose, to make shareholders rich, is now pretty much discredited. Instead business leaders are being advised, rightly, to put customers first – to do no harm – to be law-abiding members of society – to commit resources toward societal change. And the most influential proponents of this reformist movement – called “stakeholder capitalism” – are the corporate elite themselves (in the form of the Business Roundtable) and kingpin capitalists like BlackRock’s Larry Fink who wags his finger at his corporate peers, saying, “Your company’s purpose is its north star in this tumultuous environment”.

But here is where the confusion sets in. Is a brand purpose simply a lofty statement of principle? Or should it be a more prosaic “Why We Do What We Do” reason for why the brand exists? Should it be connected to what the brand actually does – or serve as a more visionary “Big Hairy Audacious Idea” that will change the world? Or maybe it should simply be a poetic aspirational statement (Apple’s credo, for example, starts with “We are here to enrich lives”). No wonder so many brand purpose statements end up as bland platitudes: no one can agree on what it really represents. Or they prefer to play it safe so no one will be offended (most of all the shareholders), watering it down to a bumper sticker slogan. Which is why purpose statements tend to be quickly forgotten.

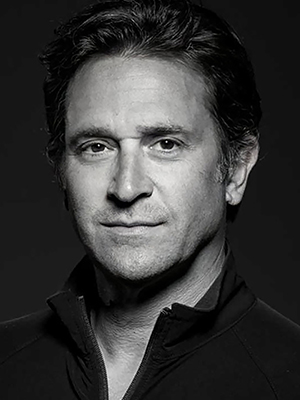

That’s a paradox Scott Goodson recognized very early on in his career – what he calls the “purpose gap” – as he helped some of the worlds most iconic Swedish brands grow into global powerhouses. Now based in New York City, his agency continues to work with leading brands to not just define their purpose, but to activate it through stakeholder socialization – in other words, to make the purpose statement come to life, both through actions and words. His latest book “Activate Brand Purpose”, which he co-authored with his colleague Chip Walker, is a handbook for business leaders to transform their companies by harnessing the “power of movements”.

I started by asking Scott how he came up with that quirky agency name.

Scott Goodson (SG): Well, the agency name was really about designing a completely different type of a creative marketing communications company. We wanted to have a focus on smaller, more agile, versus, you know, the big corporate agencies. Well, you know, I grew up in Canada. I ended up moving to Sweden when I was in my early 20s. And I worked in Sweden for a short period of time and then I ended up owning an agency in Sweden for about a decade. And what the Swedes taught me kind of built on what I had learned in Canada, which was that you don’t need a huge corporation to actually screw in a light bulb. You actually need a small group of talented individuals, and they can take a concept and they can implement it, and then they can move from that country and go basically anywhere.

When I moved to Sweden, all these Swedish corporations were starting to globalize. So I was working with Ikea, I was working with Ericsson, which at the time 60% of the world’s mobile phones were Ericsson phones, and a whole bunch of others. I worked with Stefan Persson at H&M. And as these companies started to grow out of Sweden, it all happened in the late ’80s, I ended up working with a lot of these clients. And, you know, with Ericsson, we would launch their mobile phone in the Nordics and then we would do it in Germany and then in Italy and Spain, Poland, Thailand, Australia, Brazil, the U.S., and so forth, and in Canada.

And the Swedes just didn’t believe in wasting a lot of money in big bureaucracies, big corporate agencies. So I learned from, you know, I learned strategy and creative out of Canada, and the Swedes taught me you don’t need to have a huge infrastructure to deliver great marketing on a global scale. So the idea of big corporate agency from the U.S. and the big corporate agency from the UK or the big corporate agency from France, those could be competed against. So StrawberryFrog was the antithesis of the big corporate. And we were looking for a name that was a little more original than David versus Goliath. So we looked for – there was an article at the time describing corporate agencies as dinosaurs. So we looked for an amphibian, and the rarest frog in the world is actually a strawberry frog. And so that’s where the name came from.

Stephen Shaw (SS): Very early on, it seems, again correct me if I’m wrong here, you gravitated toward this concept of “movement marketing” or “movement thinking”. What was the genesis of that idea? I know you have some background academically in social science. Was that a factor in you, you know, realizing you had something here?

SG: Yeah, I think it always was a part of who I am and where I grew up in Canada. I think growing up in Canada, you learned a lot about living in a community where you were a part of the fabric of that community, where you gave back, you know, it's very much a part of the Canadian DNA. And you notice it in a much more stark contrast here in the United States, which is a society of “me”. And I think when I grew up, I felt it intuitively and I leaned into it many times in my life. When I went to the University of Western Ontario in my last year, there was a woman from Barbados who wanted to be the president of the school and, you know, my goal at the time was to go into law. But for some reason, we were friends and she asked me if I would help her, and I said, "Okay, I'll do it." And ended up, in the year she was running for office, they didn't even mention her in the newspaper of the school, and then we ended up winning 68% of the vote. And I think the whole strategy was about the importance of, not only a woman and not only the fact that she was a black woman, but she was from Barbados. She wasn't even from Canada. And her father was a carpenter. The idea that we could take this individual who is incredibly bright and connect her with so many other individuals in Canada who also felt like they were somewhat outside of the, you know, let's say the rich and wealthy of Toronto, was a huge success. And it proved that, you know, if you think how can you help market in a more meaningful way? That was a really great lesson for me. (10.14) And then in Sweden, Sweden is also a society where they care a lot about...they are almost like the conscience of the world, or at least they were when I was there. And back in the late '80s and '90s when I worked in Sweden, consumers were demanding more of their companies. So they wanted less packaging because they thought that was bad for the environment. And they wanted more women on boards because they felt women were underrepresented on corporate boards, and decisions that were being made in these companies were being made by men and not people who were concerned about communities, and so forth. So we were doing purpose strategies back in the late '80s, early '90s for these Swedish companies. And what I saw was when we launched, for example, with Ikea, when we worked with Ikea in the Nordics, everybody understood that the brand was more than just a furniture company. But as we went outside and we started marketing in other parts of Europe, this purpose, which, you know, loosely defined was a purpose, people didn't care about it. Or they didn't understand it. They couldn't wrap their heads around it. And I saw the same with other companies as we marketed Swedish companies in Asia or, you know, in Eastern Europe or even in the U.S., people were like, "What are you talking about?" And that's where this idea of a movement came around. Like, let's not try to be too theoretical about a purpose. Because they can be a little bit too theoretical, too heady. And instead, let's use the principles of societal movements as a means of organizing people and mobilizing people to be part of something bigger. And that's when we started playing around with that idea with Ikea. And then I sold my company in Sweden in about mid-'90s and my wife and I started StrawberryFrog in Amsterdam in the late '90s but then moved back to Europe. And our first client was the Smart Car. And we had worked previously with Swatch and the Smart Car was started by Swatch and they were responsible for marketing and Mercedes was responsible for manufacturing. So we basically came up with the first client for our company was Smart, and it wasn't a new B segment vehicle. We launched it as a movement to re-invent the urban environment. And it really did a great job of separating this small two-seater from the rest of the two-seaters that were being sold in Europe. And from there we just started focusing on movements.

SS: So you've made a really key point here because one of the big takeaways for me, certainly in the book, is that the concept of movements will be the way brands are built in future. Can you just elaborate on that?

SG: Yeah, I think we're moving, I mean, it's clear that we're moving from brand to purpose. I think it's more important today if you can define what you're doing in the world, rather than, you know, just your name and a logo and some creative idea to get people to look at you. People are looking for a little more meaning. And I think a big part of that is we've moved from the era of trust; you know, when we were younger, brands talked about trust all the time. "You should trust us. You should trust our car, trust our bank." And then what technology did, it brought us closer together in ways that made us feel that we were in touch with other human beings and deep, you know, intimately in touch. And so our definition of community changed. It's not a physical community, face to face community. It's now this, you know, this engagement with other individuals over technology. We don't even think about technology anymore. And as a result of that, now we're living in a time when I think people realize that their well-being is dependent on other human beings' well-being as well. And so as a result, we're looking for a purpose because we realize that we all are not living in isolation. We're actually living very much dependent on this community and technology. So that's why I think, you know, brand becomes less important, especially no one's watching television, no one's looking at print advertising, even digital advertising, no one's looking at that. So how do you actually engage anyone? Well, I think it's about that higher, you know, higher purpose. But not just stating it, you obviously have to do it, and that's really the core of the book, "Activate Brand Purpose." How do you activate the purpose in such a way that all the different stakeholders, including consumers and customers and investors and employees, will, you know, not only believe in what you're trying to do, but help build it with you? So that's my perspective on that. (15.19)

SS: Yeah. And it's, again, you know, a really key point in the book is, and we're gonna come back to that subject of sustainability of a movement, as I said earlier. My own involvement, you run into brick walls if, as you describe it, you are not working from the middle out. But we'll come back to that subject because it's a deep one. I do want to, for people who may be living in a cave, get into a definition of purpose. Because it is confusing for people. You know, is it the why behind the what a company does? Is it the good behind the why? For purpose to work, how important is it that there's a clear connection to what the organization actually does?

SG: The best way to think about purpose is it's, you know, what are you doing in this world of ours that is beyond just making money? You know, how can you add value to people's lives beyond simply economic value? And I know everybody wants to simplify it and say, "Well, you know, what's your why and your what and your how" and all that. But I think, you know, that might be easy as a sort of traffic signals. But I think the basic idea is, you know, mission is what is the company doing on a day-to-day basis? And purpose is how are you making this world a better place? How are you making it better for your employees? How are you making it better for your customers and shareholders? That's perhaps the easiest way to think about it and try to come up with an original way to think about it. Perhaps more important to think about in a more original way, to activate it. I think the second part of the question is perhaps more important, which is, you know, is it okay just to say, you know, let's say hypothetically you're Audi and every one of your senior executives is a man. Is it okay for you to come out and say women should be paid the same as men? Well, I would argue no, because why would a car company that doesn't do what they say, why do they have the right to say it? I mean, it's ridiculous. It's like, a few years ago, there was an ad on the Super Bowl for Planters peanuts, in a similar ad, which said not paying women the same as men is nuts. Now, that would be like Snickers saying that - like, why do these brands have the right, I mean, they have the right, but why do they have the credibility that they don't? And I think that's why we have cancel culture, because a lot of people are fed up with companies trying to do business on the back of important cultural shifts and societal shifts that should happen. And paying lip service to it only undermines those situations. Like there was another one this summer where Gucci had an agenda book that was gay pride week, and there was a lot of criticism like why should Gucci sell a day book saying gay pride? It's like, what in their background, in their history or their purpose, or their brand promise is connected in anyway with gay pride? I mean, of course, gay pride is important and we should all celebrate it, but there has to be some connection to what the organization is actually doing. And I think a lot of people are sitting around and waiting for a company to not do what they say they're gonna do. And that's where I think the cancel culture comes up. So you have to have something in your purpose, something in your brand that you connect your idea to. You can't just simply state it. Otherwise, you're gonna have people criticizing the brand.

SS: Well, and maybe the truer term is business purpose as opposed to brand purpose. Because people confuse brand purpose with marketing. And let me ask you this because, you know, it's implicit, I think, in a lot of the things that you're saying. Because you have the idea of corporate citizenship, like corporations behaving as responsible citizens and doing social good. And then that gets confused with corporate social responsibility, which tends to be a department and really a PR play, etc. And I think that's where people's confusion around this comes into play. But let me back up for a second. Stakeholder capitalism, conscious capitalism, customer capitalism, Roger Martin's term, whatever you wanna call it, is that really the ideology behind movement thinking? Really the desire to transform the face of capitalism and that you have these social forces now. You’ve talked about cancel culture, but there are other forces at work, you know, trying to correct the sins of the past, if I may put it that way. Is the idea of movements part of this overall ideology? (20.24)

SG: Yeah. So I think, I mean, you mentioned Roger, I mean his whole point of view is the idea that the top of the organization is going to do all the strategic thinking and then hand it over to the organization to execute. That's, like, old-fashioned. That doesn't exist. So it's all about giving people choices, in his opinion. And he's written about that a lot. And he talks about the changing face of companies. I actually was speaking to him last week and he was talking about Porter and the knowledge worker, and he reminded me that that document was written in the 1950s. He started talking about the knowledge worker as a, you know, before that there was the physical laborer who sold his physical, you know, arm strength, leg, strength, back strength. And then the knowledge worker was coined. And it was this new era of individuals that were selling their mind, and that companies in those days had to rethink how they engaged with that person because they weren't engaging the same way as they did with the menial labor. And the knowledge worker wanted more meaningful work. And so we were talking about how that's kind of evolved and it's actually accelerated in recent years where, you know, if you're leading an organization, you're not gonna be effective if you demand compliance and you expect people to execute. You're much more sure to succeed if you bring along the organization with you, because, you know, it's not, "Do this because I tell you to do this." It's, "Let's do this because we all want to do it because it's important to all of us." So movement as a construct, a mobilizing construct in the service of some higher idea, I think is the goal, where the individuals have a role in making choices. They're not simply executing; they're being part of building the strategy with you. And, yes, executing, but they're building the strategy and doing it because they feel it's right. And a social movement is the best organizing construct for that type of way of working where you are actually inviting your employees in to help build something together. So that top-down world that used to exist no longer exists, and if you try to, for example, you know, demand compliance from younger employees today, they're more likely to give you the middle finger and go work somewhere else.

SS: You're addressing this issue of the democratization of the workplace and some fundamental management principles, but still, you know, shareholder primacy rules executive decision-making. The concept of stakeholder capitalism, acknowledged by the Business Roundtable in 2019, an inflection point, I would certainly argue. I think you argue it in the book as well. You know, the recognition that you can't continue this trend of income disparity, of these divisive social forces riven apart by this basic unfairness that exists in society. And you were addressing earlier, you know, Sweden has more social unity because they are more aligned around certain fundamental social democratic principles, but still today, and I don't mean to turn this into a lecture because it's all in your book, is today executives still think that their first and only stakeholder often is a shareholder. So how do you go from that to what you've been describing, which is the democratization of the workplace and rallying, if you will, around doing something that's more integral to the lives of people - how do you bridge that gap?

SG: Yeah, well, I think it's very clear that companies that are successful these days, they don't think in that sort of monolithic way. They think much more about the dynamism of their employees and the communities within which they live and they operate. You know, it's not simply a matter of, I mean, in some parts of the world, it is still like that where you simply negotiate lower taxes for your company to be located, but more often than not, people are looking for communities to help educate employees and to provide a healthy, you know, community for them to live in. And it's in the interest of companies to, you know, foster that. It's also in the interest of companies, I mean, on a very basic level, it's in the interest of companies to not poison people. It's in the interest of companies to educate people. It's in the interest of companies to do a lot of things that move people forward because it improves the final product. (25.35) You know, for example, here in the U.S. right now, we're, you know, Biden just passed this new bill, and they're gonna invest, you know, $350 billion in innovative sustainability industries. I mean, that's fundamentally gonna transform employees, like, the way people are educated. And they're gonna be actually rewarding companies that move into communities that will require reeducation. So for example, in the coal parts of the United States, if companies relocate to West Virginia, they will get a 10% premium on top of the money they're gonna get, because they're gonna reeducate the employees to work in sustainable fuel industries and energy industries. So there's much more of a intimate relationship between the community, the employee prospects, than there were, you know, 25 years ago. Plus, the economy is much more complicated now, and companies are looking for such diverse labor. So there's that side of it. Then, of course, I mean, there's so many different sides where companies are engaged now. They're engaged with all sorts of different groups who add pressure. Government is involved with companies these days. We see it perhaps, you know, in the culture wars, which is not really 100% representative of how government is actually working with industry. But it's an example where you see in Florida, Ron DeSantis, you know, going head-to-head against Disney. Because Disney made a stand for LGBTQ. And DeSantis is, you know, deciding he's gonna go head-to-head with that company for his own political reasons. But I think that's an example, again, of how interconnected industry is with culture, community. So many areas that, you know, when we grew up, people never thought about it. They just did it because that's what you did. So, you know, purpose and being purposeful, being thoughtful about where your employees live, how they live, what lives your employees live... like, I've spoken to so many CEOs who talk about, here in the U.S., how their employees can't put $2,000 together in an emergency. That they don't have the type of financial well-being that allows them to work in their companies in ways that they need them to work. So even U.S. monetary policy is being questioned by these CEOs who are saying it's just not enough. We really need to transform how we educate Americans in financial literacy, for example. How to save money. You know, you don't save money by buying... You don't make money by purchasing lotto tickets. It's within your paycheck.

SS: Is the really radical change though, and this moves out of a marketing discussion to some extent, is the really radical change to change the way, for example, CEOs are compensated based on stock options, shareholder value? You see all these companies doing buybacks today, instead of putting money back into the company, instead of investing in their employees. I mean, what you're describing is, you know, a very small group of companies today that adhere to these important principles. The vast majority, you know, treat purpose as a check mark, really, on their list of to-dos. There's no real dedication or commitment to it. Would you say that's the case?

SG: Well, I think there are some organizations that do put purpose at the core of their business, as you said earlier, which is really where you should put it. It's not a marketing strategy. It's a core business strategy. And there's a great book out by Felix Oberholzer-Gee, who's a professor at the Harvard Business School, it's called "Better, Simpler Strategy." And it's all about how today we have all these complex strategies you mentioned a few moments ago where you talked about CSR and so forth. And he was arguing that why is it all these big companies that have all these different strategies that are so ineffective at actually achieving much, you know? (30.06) And he was saying it's because they're just overly complicating everything. So he was arguing - and he had conversations about the idea of using purpose as sort of the highest order, you know, strategy. And because it really is highly motivating, it's beyond just simply the day-to-day manufacturing and or generating of revenue and profit. So there's a higher emotional aspect to it. And you can use that as a means of helping drive the organization, inspire the organization forward in a, not top-down model, right? Where people are supposed to be part of building the strategy together with the leadership. So I think in that type of context, where you put the strategy at the core of the business, then you have companies that are trying to do some big things. Like companies like Mahindra that are based in India where they genuinely have put purpose at the core of their business. And it's a huge industrial group. It's like if you put GE together with GM and Walmart, and you kind of try to make that a huge conglomerate. Another, I mean, there's a lot of good examples of companies that are doing this. Unilever is another one where they're really trying to put purpose at the core of the business. And I think there's some great results as, you know, because of that. I do think rethinking compensation is definitely something that should happen. I also think, I mean, we're living in a time where the problems we face are getting worse and a lot of those problems are caused by corporations and the way they do business - dirty capitalism. We're also living in a time when CEO pay is going through the roof, even in mediocre-performing companies. So something has to give. And in the book, Chip and I raised this idea of “movement shares”, which I don't know if you saw that chapter which is all about, you know, instead of having basic equity, do we start designing something called movement shares where people can start, where humans can start to buy into a company for not only their economic result, but also the positive impact they're having on the world based on their purpose being activated through movement? Like you would have a movement share. And I think those types of ideas will become more important as the negative impact of commerce and capitalism continues to show its face. So the negative impact of the oil and gas industry, the more we have fires and floods and unseasonable weather. I was in Europe this summer and it was intolerable how hot it was in Southern Europe. I mean, we're living in a, you know, a cataclysmic period right now. It's just starting. And I think as that intensity increases, people are gonna start demanding a hell of a lot more. So that'll come to come to be, I think, in the future.

SS: Well, and I think ultimately too, changing the composition of boards so there's greater diversity of voices and labor workers being acknowledged obviously needs to be considered too. But I just wanna deal for a moment, you know, when we're talking about the forces of capitalism. You've got, you know, a fairly reactionary element, whether it's activist investors, or skeptics. So let's take two prominent ones. You referenced them in the book, Byron Sharp and Mark Ritson. They've both been harsh critics of brand purpose. What do you make of their revanchist opinions? Are they really just complaining about the fact that marketers are papering over really what is an advertising campaign with lofty language? Where do you think their opposition is coming from?

SG: I mean, they're thinking of it as a marketing platform, but it's not a marketing platform. I think capitalism is the most successful economic system to ever exist, but it's destroying the planet. So if we don't, I mean, leaders are understanding. You mentioned Business Roundtable. I mean, they understand it. Doug McMillon, the CEO of Walmart who's the chairman of that, he understands it. And companies are starting to work towards it. There's still a long way to go and, you know, questioning what's wrong with modern capitalism and how do we develop a roadmap for how business can help to create systemic change that we need, I think that is the question that purpose can answer. Byron Sharp is wrong in that it's a marketing platform. It's not a marketing platform. It is a business strategy for how business can conduct itself in a way that works for everyone rather than just for the few. (35.04)

SS: But to your point in the book, you also, and we talked about this earlier, it also can be a brand differentiator in a commoditized marketplace. You use Tesla as an example.

SG: Yeah, it can. It can, but I'm saying as the core idea in terms of his criticism of about purpose, I think Byron Sharp's criticism is it doesn't work necessarily as a... it shouldn't be a marketing platform. And I agree with him, it should be a core business strategy. But it can also be a highly motivating idea for a purchase. It increases the willingness for people to buy from a company, and it increases the willingness for people to work for a company. If you have a stated purpose where, for example, in the Tesla case, you're using innovative energies, bringing new power to the world, to, you know, to mobility, to your home, that's an inspiring thing. And I think a lot of people look at Tesla and they say, "Well, okay, Elon Musk is kind of out there doing weird stuff, but the company is actually doing good." And I think people who drive Tesla, I don't think they look at Musk, at least not today, I think maybe in the past they did, but I don't think they look at him and see him as the equivalent of Tesla. They see him as an individual and they see Tesla as this purpose-driven organization using electricity to innovate new mobility solutions. And they see Tesla as an innovative company coming up with home, like, you know, power solutions. And I think that's highly motivating, for people to buy Tesla. I don't think they're buying it because they think, you know, it's not like it was with Steve Jobs and Apple where Steve Jobs was the spokesperson and people bought because they love Steve Jobs. I think Musk and Apple, sorry, Musk and Tesla are connected, but I think people don't buy Tesla because of Musk. I think they buy it because of the fact that they're these really cool, innovative, alternative electric vehicles.

SS: And we're gonna get to the Purpose Power Index in a second, but you do reference that difference between Tesla and SpaceX as an example to support the point you were making. I just don't wanna move off just quite yet the role of marketing here. Now, marketing's lost its voice in the executive suite. It's no longer viewed as having any gravitas, any influence on strategy, in fact. But it seems to me marketing being closest to customers, or at least closer to the customer insight required to get to what ultimately that purpose is, is really essential to success here. But how would you describe the role of marketing in this process of landing on the right purpose, on ultimately activating it, as you put it?

SG: I think marketing is an area within a corporation that are used to using language and communications to express an idea, versus let's say finance, where they use numbers, which are not easily accessible by everyone in the organization. So if you forget about marketing from, let's say, a role that has to grow a brand or a business, but rather its function inside the organization to help communicate ideas, I think that's why people connect purpose with marketing. Because it takes what is in fact a business strategy, and makes it emotional and easy to understand, and motivating. Marketers are good at communicating, good at writing. And they think about that. So I think that's why it sits in that department. I think purpose-activated is the big challenge. You know, that's what the whole book is about, that companies, you know, everybody has a purpose these days, but they're all toothless. Many of them are toothless, and they haven't been activated either inside the organization towards their employees, or outside the organization to their different stakeholders, including customers. And that's really the challenge. How do you take a purpose and then activate it in an original way so that it becomes the thing that increases people's willingness to buy from or work for a company? (39.37)

SS: Well, and that's the really original part of the book as you even say. I think in one part of the book there's scores of books on brand purpose, you know, on my bookshelf, there's seven or eight, but they're very process oriented. They don't actually describe what you actually need to do in the long term to succeed and make it sustainable. And that was, for me, a big takeaway from the book, the degree of commitment.

SG: And every chapter we've written towards a specific function in the organization. So you have a chapter around the CEO and we have a chapter on the CFO. We have a chapter on the CMO and a chapter on the head of HR, or a chief people officer. So we're trying to use, like, the C-suite and say, "Here's how you can activate purpose in your area." And we use examples of where we've done that with different, you know, companies and different leaders. And I think that's, for us, was the way to, you know, showcase the how to activate it yourself. Here's some examples of how you should think about activating it. If you're a CEO of a company, you know, what should you do? If you're the CFO, what role do you have? I think that's really the key thing. How do you break open the company and give all these leaders really clear recommendations for how they can work, and examples of others who've done this very well?

SS: It is a formidable undertaking, you know, when you put it all together. And many organizations don't have the persistence, I guess I would describe it that way, to really carry through with it. And as you point out, it peters out after, you know, a year, a year and a half. Which brings me to the Purpose Power Index, because isn't that the essence of the index, to evaluate the sustainability of that brand purpose? You've got a company called Seventh Generation, which many people may not be familiar with, a cleaning company, topping the rankings. Can you just explain briefly how the Purpose Power Index is created? And I know you used RepTrak as part of this exercise, and why Seventh Generation ended up being the top company amongst the top 100 that you name in the book.

SG: Yeah, so when we started focusing on activating purpose with movement thinking, which is what we do at StrawberryFrog, we wanted to have some kind of monitoring system that we could measure the impact of purpose, both among consumers and employees. Because we say that's really where purpose makes a significant impact, or we believe it does. And there was no empirical study of purpose anywhere in the world. So we basically created the first measure of purpose brands or purpose companies. And we spoke to 20,000 U.S. consumers, which is a significant study, and through that study, we were able to rank the 100 winners and laggers as it relates to purpose. And when we talk about purpose, we use the definition that I said earlier in the program, which is a company that's doing more to make the world a better place, or beyond simply economic value. And we then had those 20,000 people, you know, mark brands out of a list of - I can't remember how many there were, 400 - mark companies that they felt were purposeful. And Seventh Generation was number one. And I won't name who was the last one marked, but there...

SS: Well, that was going to be a question, actually.

SG: Yeah. We call them winners and laggards. The laggards, many of them were technology companies who I think, you know, kind of let us down a little bit. What I mean by “let us down” was back in the early 2000s, we all thought that technology companies were gonna usher in a new era of democracy and help bring about a more equitable society. And what we realized is no, they're not. They're actually self-serving and they're quite the opposite. They're......mercenary. And I think a lot of people are, and parents of children who use social media and those types of things just realize, and people living in society who see what's going on all around is realize that this is really quite toxic. And so I think a lot of the negative came from that. I think Apple did better because of their stand for privacy. And I actually believe if they were to lean heavily into that, that they could become the technology company who would be most admired. Because at the moment, I think all of them are being seen in the laggard space. Which is, and it actually goes to the point I made earlier, which is we're moving from brand to purpose, where people are putting great value on companies that are doing these, you know, positive changes in the world. And, you know, remember what Apple was like in 1995, you know, it was a cool company. Well, it's not enough just to be a cool company anymore. You have to be doing something. Anyway, in terms of that measure, that's what was clear. (45.30)

SS: And one of the surprises for me was that Nike didn't make the top 100, I think they were 165th out of the 400 or so that you named. And yet, you know, a lot of people looking at it from the outside would say, "Geez, there's a company where its purpose is clear to everyone." Why the low ranking for Nike?

SG: I mean, I can’t answer for why people answered the research the way they did. There was, as you may be familiar with, some criticism. Nike, during the George Floyd murder, and then the social unrest that happened where Nike came out in support of that. And then it turned out that none of their senior executives were African American. And so I think it perhaps was an example of where the advertising perhaps didn't reflect the actual way the company was organized. And when I said at the beginning of this program, there are people standing around waiting for companies to not do what they say they're doing. And it's not enough just to have cool advertising. You really need to walk the talk. You need to do what you say you're gonna do. If you're Audi and you're gonna stand for women having equal pay as men, you need to have women on your executive team who are making the same as men. You can't simply put an ad out saying, "Hey, buy an Audi because we believe that women should be paid the same as men."

SS: So you've mentioned Unilever. Unilever is on your top 100, Ben and Jerry's is on the top of the 100. I'm sure you're familiar with the spat that's going on between them now with Ben and Jerry's accusing Unilever of undermining their social mission with the sale of their Israeli business. Yet this is the same Unilever that wants every brand to have a distinct social purpose. Is this what happens though, when purpose starts to collide head on with the idea of profit over purpose?

SG: Look, I think everything in business and in our lives is becoming a lot more complicated than it used to be. Everything is interconnected in some way or another. And I think companies are trying to take stands on important social issues. I think some of those issues are causing companies to backtrack. And I don't want to spend time, you know, evaluating whether that's the right decision or wrong decision, it's up to those companies to make those decisions. I do think it is a good idea for companies to have purpose as core business strategy for all of their brands, because I do think it will make the organization more successful and profitable and do good, which is what we need them to do. And if you do good, they will do well. And, you know, there was a lot of criticism a couple of years ago of Unilever that their performance wasn't as good as it should be. But actually, if you look at the brands that were purpose-driven, they actually had a significantly higher return on investment than the ones that weren't. So actually, the evidence is in the contrary. And you know, there are a lot of people standing around, you know, we're living in this era where everybody wants to gang up and point a finger and show how bad everyone is. There was an example a couple of years ago where … they had a CEO who was terminated because he came out and said he wanted to have a purpose-driven corporation. Well, the problem there was he had poor financial results and he was using this purpose as a way to cover up that. But they conflated the two and said, "Well, because he was focused on purpose, he had bad economic results." No, that's not the case. So he had a lot of detractors standing up on the side, throwing rocks in. Like anything, like climate change, like all this stuff, you know, there's a lot of people with their own agendas.

SS: Well, for every movement there is a countermovement.

SG: There can be, of course. Yeah.

SS: I mean, you look at, you referenced Nike earlier and the Kaepernick reaction, although that turned out well for Nike in the end because it knew its customers. And I think that was Phil Knight's quote is, you know, it's, "I don't care what those folks are. They're not buying my product. So I only care about the people who have loyalty and love the brand. And that's why I'm doing this." And it was a very, I thought, courageous and bold move on their part, but tough to do, unless you're a Phil Knight, a co-founder of a company. (50.12)

SG: I mean, it's hard to do it, even if you're an officer of a public company. And, you know, you have to do something like a lot of companies did when they passed these border restriction laws in Georgia and they pulled out of the all-star baseball game. Or when Disney took a stand for LGBTQ rights in Florida, that's a equally difficult, that's a public company run by an individual. I think it's hard to make a stand for something that's important. And companies that do will be criticized and then they're rewarded. I think ultimately Disney will prevail because I don't think what DeSantis is doing will succeed legally. And Disney will have demonstrated to a large group of people that they are, you know, embracing a diverse community that also, by the way, happens to be a large part of their employee base. And, you know, they can't cut off those individuals, those people, those human beings, just because a political group wants to do so. And I think where purpose comes in, it comes in when there are crises. It comes in when there are needs to move quickly on issues. I'll give you an example. We worked with an extraordinary individual who leads a financial institution in the U.S. It's the sixth largest bank called Truist. And it was a merger that happened just prior to COVID, and purpose was developed. We've been working with them since the inception of this new organization. The purpose was actually written by the CEO and his C-suite. They wrote it, and the purpose is inspiring and building better lives in communities. Now, it's a great idea on the simple basis that it focuses on the customer as opposed to the products. And it goes beyond the customer. It focuses on the communities within which they live. And the role of this organization actually to build a better life for you as a customer, but also as employee, and also the community within which you live. That was their idea. Five minutes after they wrote that down, COVID happened. They were the first bank in the United States to come out with a comprehensive program, to put money into the communities to keep people moving, to keep businesses going despite the fact that everything's shut down. It took other banks months. So the purpose allows you to move quickly in a crisis situation. Now, I can't pinpoint Nike's Colin Kaepernick example as something that would come out of a purpose, but it might. If you had something like that, and if you didn't have that kind of charismatic leader like you have in Phil Knight, again, you have a public company where you have a CEO, a purpose, and a movement forms that similar type of framework that you then can have others in the organization make choices and judgments. And have constraints so that they can make decisions that will move the organization forward in a crisis situation in a positive way. And I think leaders are becoming more aware of that right now.

SS: And they don't wanna be seen as pariahs, you know, they have large egos. So they'd rather be seen as a hero than a villain.

SG: Or flatfooted if you're...or even late. I mean, it was a competitive advantage for this new bank to come out and move the way they did in those communities. Those communities now consider them... they're highly regarded because of their behavior during those first few months of COVID.

SS: We have a short amount of time remaining and I just wanna come back to something I alluded to earlier, which I think was a strong takeaway for me from the book, is this idea of “middle out”. Which is you need buy-in from you know, your middle management. There's a concept called air sandwich where a lot of corporate strategies never succeed because basically, middle management rolls their eyes and acts passively toward it. And brand purpose falls victim to this, as you describe in the book. But my question here, and this is the “lift the hood part” is, God, it's gotta be hard to build a broad consensus, especially if you have a large employee workforce where there's likely to be this polarity of worldview. So everyone who holds up their hand and says, "Yeah, I can get behind that," will be somebody else who says, "No, I can't, I disagree with that." How do you iron out that consensus and ultimately arriving at a purpose or a movement as you describe it, that everyone can truly get behind without it being too diluted? It's gotta be a tough exercise. (55.14)

SG: You know, the most difficult challenge is when you work with a very intelligent group of people. And we just finished launching a new piece of work for a challenger brand in the consulting, public accounting, and technology space. It's a company called Crowe, C-R-O-W-E. And we worked with many, many of their internal teams to develop this big idea for them. And in working together with the different leaders, departments, and people within the middle of the organization, we were able to come up with an idea which is called “embrace volatility”. And it's this idea that because they're a, you know, a public accounting consulting company, they work with clients, public professional services company, they work with clients. How do you make them relevant? And how do you give them a real role, a relevant role in today's world? And what we said was, you know, this idea of volatility, uncertainty that we're living in, which is only increasing every day is a real conundrum for business leaders. And we want to be the organization that helps leaders see opportunity in crisis, as opposed to fear and worry. Because if you're fearful, you can't lead an organization through a difficult period. But if you see opportunity and you're working with this international, you know, it's a very large U.S. team, but then it's an international team, if you can work with this consulting firm as a leader, you can navigate this economy we're living in without being at the mercy of it. And that is a really big and original idea to get through that kind of an organization, you know, because that sector is full of placid ideas. And we did it because we were able to almost use the movement framework in building the actual idea where people were participating in developing the strategy with us.

SS: So you're saying here that it's really important to have a grassroots component to this?

SG: Yes, absolutely. It's no longer the time where you work with a tiny group of people in the marketing department and then launch it. Because then it will become that middle sandwich that you said. You instead need to build it together with all the different folks that you're trying to bring on board. Because they give you, like I said, you can't divide the company between the top of the company who are the strategy people and the rest of the company that are just gonna execute. That's where you're gonna get your middle sandwich. You need to have people building the strategy with you and providing input into it.

SS: And the other thing that, again, is a takeaway for me is a triangulation here of customer, community, the values that you espouse, the citizenship part, if you will, of being a corporation, those have to be totally aligned for all of this to come across as authentic. Would you agree?

SG: Absolutely. I mean, look, the world is full of problems to be solved. And each one of those represents immense opportunity for businesses. So why focus on ideas the world doesn't need when there's good business solving problems? To me, that's the crux of purpose.

SS: So final question, and you've been very generous with your time today, but how would you describe the purpose of your agency?

SG: Our purpose when we started was creativity for good, which was all about creating good results for our clients, good results for our Frog teammates, and good for the world. And so, everything that we've done since we started this organization, whenever we're developing a new idea, has been with that in mind, is how can we bring that higher level of positive contribution to our clients? And sometimes without them wanting it or thinking about it but having an open conversation with them where we say, look, like I said earlier, you know, it's not to your benefit if you're making your people sick or you're making your people less, you know, poorer. They should be financially better off. They should eat good food. Their children should live in comfortable, confident, secure communities. And more often than not, the leaders of those companies will agree. And they'll say, "Yes, we should try to do that." And many times they don't think about it. So I think that purpose drives us in everything that we do. (60.0)

SS: Right. But you're not writing headlines. You're change agents, really, in most respects.

SG: Yeah. Change agents working with leaders that want to put purpose at the core of their business. And so, you know, half our business today is something we call Movement Inside, which is basically we work with leaders to do purpose-driven transformation of their employees inside large corporations. We're doing this with Walmart, we're doing it with Pfizer. We work with huge companies. And then the Movement Outside, which is the legacy business is the, you know, is like marketing and advertising, but with movement. So Movement Inside is an internal purpose-driven transformation and then movement outside is external marketing. All using purpose as the core for the activation. And the marketing aspect doesn't necessarily have to be advertising or, you know, paid media. It can be actions. It can be events, and things like that.

SS: Well, Scott, this has been everything I expected it to be, a wonderful conversation. I just love the book, the books, as the case may be, and love this conversation. So I'm so behind it too. I thoroughly, you know, subscribe to everything you've been saying here. It's fantastic. It's a change too from, you know … the focus of customer-first thinking is marketing transformation and putting customers first obviously has been a stepping stone. But this aspect of it rallying around a North Star, a beacon for the organization is really fundamental to success here. So very important work that you're doing.

SG: I've been doing this for like 30 years and, you know, I really like Byron Sharp. I just used him as an example. But, you know, he's written some wonderful books with great ideas. I think he's an academic and I'm a doer. I've spent my life building purpose-based businesses around the world. And I've stood beside leaders such as Anand Mahindra in India with Mahindra, or Mr. Onitsuka, or Kazuo Sumi, who's the CEO of Asics, or the founders of Natura in Brazil or Truist in the U.S. And when you stand beside a leader who's implemented a purpose and he sees the impact of that purpose with their employees and with their customers, you see the impact that you can make. And you also see successful organizations. So with all due respect to Byron, who I also think is a very bright individual, I do think purpose matters in marketing, but I do agree that it should be at the core of the business. So I land on that note.

SS: Perfect ending. Perfect ending, my friend. Listen, as an ex-Montrealler, I'm very proud of you and the work you've done and the legacy you've created for yourself. So, just huge admirer. So thank you for the time you've given me today. I feel very honored, the fact that you gave me time today. So I very much appreciate it.

SG: It's a pleasure.

That concludes my interview with Scott Goodson. As we learned, there is a purpose to having a purpose. Mainly, to get everyone in the company marching to the same tune. And that tune is about making the world a better place. A tune everyone is willing to enthusiastically sing along with because they believe in the purpose. That purpose must come from the heart - because that is the only way it will ever become the heart of the business. And it can’t originate at the top of the corporate hierarchy. It has to be organically grown. It has to start with a grassroots mobilization – forming a groundswell of support that grows over time into a sustainable movement. And that is only possible if the brand purpose gives everyone greater meaning in their work - if it benefits the community at large, not just the owners and shareholders. Purpose, in short, is good for business, because business will be seen as doing good. You can find past episodes of this podcast on CustomerFirstThinking.ca where you’ll also find articles, strategic frameworks, video and more on the transformation of marketing. In closing, a big shout-out to my friends and colleagues Justin Ecock and Shak Rana for their contribution to making this podcast happen. Until next time, thanks for listening.