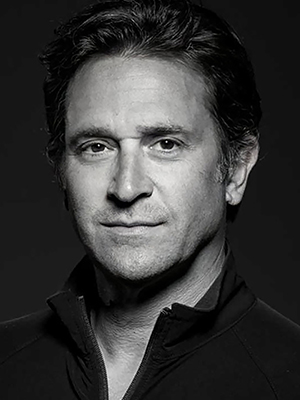

Scott Goodson is the Founder and CEO of Stawberry Frog and the co-author of the book “Activating Brand Purpose”.

Practically every corporate boss these days has it on their to-do list – coming up with a business purpose beyond making money. Most of the time they feel it’s a bit too touchy-feely an assignment when the only thing they really care about – what they get handsomely rewarded for – what the board and shareholders and financial analysts expect of them – what they were trained to do in B-school – is generate faster growth and higher earnings. But they also feel the growing public pressure to position their business as a socially responsible corporate citizen. To be seen as heroes and not villains. And so they go through the motions of defining their business purpose.

The CEO might choose to hold a facilitated retreat amongst the executive team and define that purpose behind closed doors. Or the job might be handed to marketing, thinking it’s nothing more than a public relations initiative. Or they might mistake it for a Corporate Social Responsibility campaign. The outcome, in every case, is exactly the same: a lame purpose statement followed by an ostentatious launch event and internal rallies to inspire the troops, accompanied by some external fanfare, just so the public is aware. But then that initial surge of enthusiasm fades away. All that is left, a year or so later, is a wall poster, a revised “About Us” page on the web site, and communication slogans from a now dormant ad campaign. Back to business as usual.

No wonder the critics of brand purpose are so shrill in their opposition to it. The acerbic Marketing Week columnist Mark Ritson calls it “moronic”. Another equally churlish marketing expert Byron Sharp accused proponents of learning their economic history in art school. And of course activist investors loathe the idea. Even Unilever, whose commitment to sustainability is undisputed, came under attack, mocked by one large equity investor as “losing the plot”.

Yet, despite the nasty criticism, there is a business purpose to having a brand purpose. Because the public perception today is that corporations are the enemy, responsible in one way or another for many of the ills in society, from growing income disparity to workplace discrimination to environmental pollution. So corporate reputations are at stake. Companies which act as pariahs just put social stability at risk which is never good for business.

The long-held Friedman doctrine that business has only one purpose, to make shareholders rich, is now pretty much discredited. Instead business leaders are being advised, rightly, to put customers first – to do no harm – to be law-abiding members of society – to commit resources toward societal change. And the most influential proponents of this reformist movement – called “stakeholder capitalism” – are the corporate elite themselves (in the form of the Business Roundtable) and kingpin capitalists like BlackRock’s Larry Fink who wags his finger at his corporate peers, saying, “Your company’s purpose is its north star in this tumultuous environment”.

But here is where the confusion sets in. Is a brand purpose simply a lofty statement of principle? Or should it be a more prosaic “Why We Do What We Do” reason for why the brand exists? Should it be connected to what the brand actually does – or serve as a more visionary “Big Hairy Audacious Idea” that will change the world? Or maybe it should simply be a poetic aspirational statement (Apple’s credo, for example, starts with “We are here to enrich lives”). No wonder so many brand purpose statements end up as bland platitudes: no one can agree on what it really represents. Or they prefer to play it safe so no one will be offended (most of all the shareholders), watering it down to a bumper sticker slogan. Which is why purpose statements tend to be quickly forgotten.

That’s a paradox Scott Goodson recognized very early on in his career – what he calls the “purpose gap” – as he helped some of the worlds most iconic Swedish brands grow into global powerhouses. Now based in New York City, his agency continues to work with leading brands to not just define their purpose, but to activate it through stakeholder socialization – in other words, to make the purpose statement come to life, both through actions and words. His latest book “Activate Brand Purpose”, which he co-authored with his colleague Chip Walker, is a handbook for business leaders to transform their companies by harnessing the “power of movements”.

I started by asking Scott how he came up with that quirky agency name.

Scott Goodson (SG): Well, the agency name was really about designing a completely different type of a creative marketing communications company. We wanted to have a focus on smaller, more agile, versus, you know, the big corporate agencies. Well, you know, I grew up in Canada. I ended up moving to Sweden when I was in my early 20s. And I worked in Sweden for a short period of time and then I ended up owning an agency in Sweden for about a decade. And what the Swedes taught me kind of built on what I had learned in Canada, which was that you don’t need a huge corporation to actually screw in a light bulb. You actually need a small group of talented individuals, and they can take a concept and they can implement it, and then they can move from that country and go basically anywhere.

When I moved to Sweden, all these Swedish corporations were starting to globalize. So I was working with Ikea, I was working with Ericsson, which at the time 60% of the world’s mobile phones were Ericsson phones, and a whole bunch of others. I worked with Stefan Persson at H&M. And as these companies started to grow out of Sweden, it all happened in the late ’80s, I ended up working with a lot of these clients. And, you know, with Ericsson, we would launch their mobile phone in the Nordics and then we would do it in Germany and then in Italy and Spain, Poland, Thailand, Australia, Brazil, the U.S., and so forth, and in Canada.

And the Swedes just didn’t believe in wasting a lot of money in big bureaucracies, big corporate agencies. So I learned from, you know, I learned strategy and creative out of Canada, and the Swedes taught me you don’t need to have a huge infrastructure to deliver great marketing on a global scale. So the idea of big corporate agency from the U.S. and the big corporate agency from the UK or the big corporate agency from France, those could be competed against. So StrawberryFrog was the antithesis of the big corporate. And we were looking for a name that was a little more original than David versus Goliath. So we looked for – there was an article at the time describing corporate agencies as dinosaurs. So we looked for an amphibian, and the rarest frog in the world is actually a strawberry frog. And so that’s where the name came from.

Stephen Shaw (SS): Very early on, it seems, again correct me if I’m wrong here, you gravitated toward this concept of “movement marketing” or “movement thinking”. What was the genesis of that idea? I know you have some background academically in social science. Was that a factor in you, you know, realizing you had something here?